The Bloodhound SAGW played a crucial role as a component of the UK's air defence during the "Cold War".

This Bloodhound article by Paul Jackson appeared in the Royal Air Force Year Book 1990:

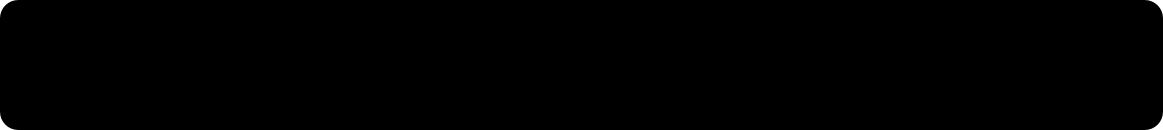

Unfortunately, despite his positive comments, not long after the fall of the Berlin wall the Bloodhound Mk2 system was scrapped. More ominously, nothing better has taken it’s place to this day.

The article pages, which can also be read on the superior radar web site, www.Radar Pages.co.uk, were scanned into a wordprocessor using Omnipro 15 software and expanded and tidied up into a more read-able form.

It reads as follows:

Which RAF interceptor entered service before the now-retired Lightning, yet will remain in front line use for some years yet?

The answer is not a manned aircraft - which most people immediately think of - but a missile which silently guards the approaches to Southern England every minute of every day. Like the faithful creature after which it is named, the Bloodhound SAM (Surface to Air Missile) stands prepared to track down any intruder encroaching upon its territory.

In the fast-changing world of aerospace, it has become fashionable to decry any system more than a few years old, the implication being that it is outdated and ineffective. 'Not so' say the men and women responsible for keeping the Bloodhound Force operational as an effective 'goalkeeper' to the fighter aircraft of No 11 Group, RAF Strike Command. Thanks to an ongoing programme of refurbishment and modernisation, the six East Coast flights of Bloodhounds remain the only truly instant, all-weather interceptor force in the RAF.

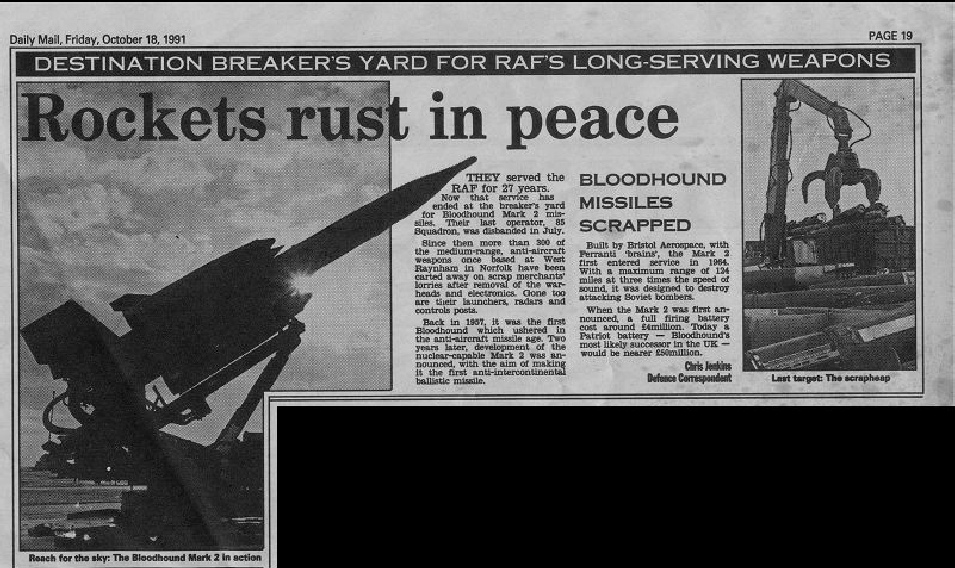

Deployment of the Bloodhound Mkl began in 1958 at the culmination of a development process begun a decade earlier by the Bristol Aeroplane Co (now part of BAe) and Ferranti Ltd - the latter providing the radar guidance and control post. Bloodhound 1 was used to protect the V-bomber bases and was usually installed nearby. It had a range of 40 miles (64km), but its pulsed radar could be jammed and was vulnerable to ground 'clutter', thus degrading low-level capability. These short-comings were quickly tackled, resulting in Bloodhound 2 joining the RAF in 1964.

Bloodhound was also stationed abroad, and in 1970 (after the Royal Navy had assumed the strategic deterrent role) all systems within the UK were withdrawn and either stored or transferred to RAF Germany, where No 25 Squadron had moved for aerodrome defence. Changing operational requirements later prompted a re-appraisal of this policy in the light of the low-level threat, resulting in No 85 Squadron forming at West Raynham, Norfolk, on 18 December 1975. Now the home of the Bloodhound Force, it had its first missiles operational with 'A' Flight and assigned to NATO on 1 July 1976.

New deployment plans called for the Bloodhounds to form a barrier, rather than a point defence system. Accordingly, March 1976 saw 'B' Flight form at North Coates, near Grimsby, whilst 'C' Flight was installed at Bawdsey (the historic site of the RAF's first radar station), near lpswich, in July 1979. With the Thames-Humber line established, No 25 Squadron returned home from Germany between 1981 and 1983 to fill-in the gaps: 'A' Flight at Barkston Heath, Lincs; 'B' Flight and HQ at Wyton, near Huntingdon; and 'C' Flight at Wattisham, Suffolk. On 1 October 1989, No 25 Squadron became a Tornado interceptor unit at Leeming, and its bases were inherited by an expanded No 85 Squadron:

D/85 at Barkston, E/85 at Wattisham and F/85 at Wyton.

Bloodhound remains in service simply because it is still an effective system. Once dedicated to high-level interception, it has been switched to lower-altitude targets with little fuss other than mounting its radars on towers to give them an improved view. Radar energy (continuous wave, replacing the Mk l's pulsed) reflected from the target is received by a dish antenna under the missile's nose cone and the Bloodhound is directed towards the point in the sky at which the enemy aircraft will be intercepted. Changes in direction are achieved by moving the two wings in the centre of the missile body either differentially or in unison: the so-called 'twist and steer' principle.

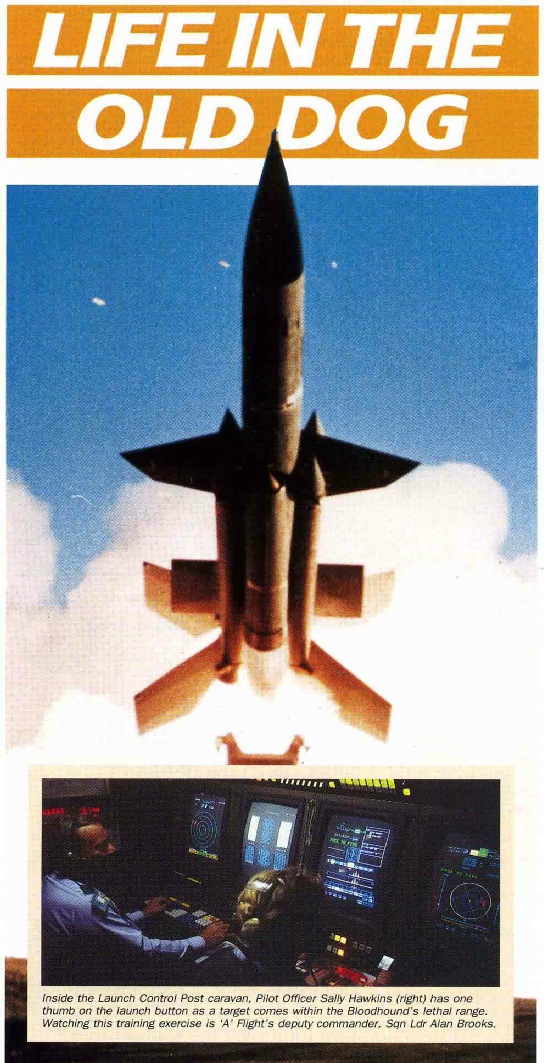

Sports car aficionados, to whom '0-60' times are of great interest, may care to contemplate the fact that on launching Bloodhound achieves 0 to 760 (1,220 km/h - the speed of sound) within the 25ft (7.62m) of its own length.

Four seconds later, the four RoF Gosling solid-propellant boost rockets have accelerated the missile to Mach 2.5 and fallen away. By then, the two Bristol Thor liquid-fuel ramjets are working to sustain the SAM during a flight of up to 80 seconds. Having been mounted on a ramp inclined at 34deg 30' the weapon will now probably be far above its quarry.

Four seconds later, the four RoF Gosling solid-propellant boost rockets have accelerated the missile to Mach 2.5 and fallen away. By then, the two Bristol Thor liquid-fuel ramjets are working to sustain the SAM during a flight of up to 80 seconds. Having been mounted on a ramp inclined at 34deg 30' the weapon will now probably be far above its quarry.

Tipping over on its nose, it will dive on the victim, guided by the reflected radar energy still originating from its launch pad scanner. The maneuvering tricks for making pulse-Doppler radar break its lock do not work for continuous wave, whilst attempting to jam the radar can be counter-productive unless done with great circumspection, as the Bloodhound has a 'home-on-jam' facility.

Detonated by a proximity fuse, the warhead explodes to scatter a shower of metal rods which form, effectively, a 120ft (37m) circular-saw spinning through the air. Precise details of range are secret, but published data refers to a radius of 50 miles (80 klm) - the Mk2 carries more fuel and target heights up to 59,000ft (17,980m) and well below 1,000ft (305m).

The men and women who operate and service 'The Dog' come under the Bloodhound Force Commander (BFC), who is also the station commander at West Raynham. As the top link in the command chain, the BFC works in the Force Operations Room and is in direct contact with the Southern Sector Commander at Neatishead, the underground bunker which co-ordinates air defence forces south of the Humber. On the next rung down are the six Bloodhound Flights, each of between two and four Sections.

A Section controls six to eight launchers and one radar from its Launch Control Post (LCP) caravan. A back-up stock of missiles is held close-by, ready to be bolted on to the launcher by a side-lifting vehicle. Communication of orders and information between all levels of the command have been expedited by newly installed Auto Data Processing (ADP) system using Hewlett-Packard HP1000A hardware and BAe -designed programmes. ADP extends down to the six operations rooms of the Bloodhound flights, the first to be so equipped commissioning late in 1987. Data presented on screen includes details of potential targets acquired, individual weapon readiness and engagement status.

The Force Commander can therefore see the whole tactical picture as a computer-generated map and also call up any one of over 100 pages of engineering status data on the Bloodhound force. If any site is put out of action, the others are quickly able to assume its functions.

LCPs have their own power generators and air conditioning - but the latter is for the benefit of the computers, not the staff! Here, the number-crunching is performed by a recently installed Ferranti Argus 700 computer which processes radar data and checks-out the serviceability of the Bloodhounds on their pads. Appropriate data is displayed on screens monitored by the officer or NCO Engagement Controller and his or her SNCO technical assistant.

The LCP is, from the outside, no more sophisticated than a caravan protected by an earth revetment. This is deceptive, for the caravans are just completing a refurbishment programme which includes a complete re-build with the new computer and consoles. Similarly, the Ferranti Type 86 Firelight I/J-band radar caravans are being gutted and stripped down to bare metal before renovation under a contract due to be completed by the middle of this year.

In the past, No 85 Squadron had the fixed-base Marconi Type 87 Scorpion and No 25 used air-portable Type 86s. For reasons of economy, the force has now standardised on the T86 - even though mobility is not required - because additional second-hand equipment of the same type was available from Sweden and the retired Thunderbird SAMs of the British Army. West Raynham went over to T86 in 1986 and was followed by the coastal stations of North Coates and Bawdsey in 1988. The other three bases, of course, have had that radar since establishment.

Inland-based units have their radar on 30ft (9m) towers, but coastal units use the 14ft (4m) base of the old T87 which, because of its shape, used to be known as a 'Dalek'. It may seem curious, yet is entirely logical, that each Bloodhound missile section is treated like an aircraft - to the extent of having its own 'Form 700' which is handed to each Engagement Controller coming on duty.

Every year, missiles receive a Minor Overhaul, and every two years undergo a more searching 'Major', this work being carried out at West Raynham's Missile Servicing Flight for all except the North Coates Bloodhounds (which have their own facility). Because the weapon is fuelled and armed when on the launcher, safety dictates that only minimal servicing can be accomplished in situ. If an 'on-line' signal fails to show on the missile status screen in the control post, the round has to be made safe before removal indoors for technical examination.

Electronic check-out equipment will find any fault in the circuit boards, but there ends the parallel with modern electronics. Instead of plugging in a new board and dispatching the old unit elsewhere for repair, as on a Tornado squadron, the Bloodhound technician plugs in his soldering iron. Throw-away technology has yet to reach No 85 Squadron, and the result is Servicing Flight staff who have the job-satisfaction of being able to follow a fault through from diagnosis to rectification with their own hands.

After 25 years of service, the Bloodhounds are now receiving a well-deserved refurbishment. Despite having been lashed by the elements for the greater proportion of this time, they have resisted well, although just to make sure, each is completely dismantled and stripped of paint. Other programmes have included overhaul of ramjets, nosecones and warheads, plus removal of aluminium covering from the wings to reveal the wooden core for a corrosion check. (The RAF could never live down reports of dry rot or woodworm infestation in its front-line equipment.) Missiles not immediately put back on launchers are kept in the external Ready-Use Missile Store, connected to a pipe which constantly passes dried air through their electronics.

Nearby, Bloodhound launchers supply the same service to ready-to-fire rounds from an air conditioning unit. Also part of the launcher are an electronic power supply and a hydraulic pack to rotate the launcher and power the missile's controls during the first few seconds of flight. Observers have attached great political significance to the fact that all Bloodhounds point East but, in fact, they are simply turned to have their backs to the prevailing (westerly) wind when not at readiness. Called to action, the six or eight weapons of an LCP rotate in unison to point where the Type 86 radar is looking.

Weapon, Airframe, Propulsion, Air Radar and Air Defence technicians pass to and from the Bloodhound Force during their service careers, just as if it were an aircraft -operating unit. Similarly, though volunteers to 'pilot' a Bloodhound in the accepted sense of the word are notoriously scarce, the closely-approximating Engagement Controllers were previously drawn mainly from the same General Duties (Air) Branch of the service. Now, almost all those responsible for launching Bloodhound are fighter controllers, to be augmented in the future by a few personnel from the RAF Regiment. Since 1980, women have been joining the ranks of Controllers, the first of them (FIt Lt Fiona Barnes) gaining the further distinction in November 1986 of becoming the first woman to launch a live Bloodhound for a random reliability test. (This, of course, was done at the Aberporth missile range in Cardigan Bay against a Jindivik drone.)

Every minute of the day, every day of the year, there is at least a nucleus of personnel ready for action at each Bloodhound site. The Engagement Controllers maintain proficiency by tracking the plentiful air traffic in eastern England or using the training facility which, with the simple change of a computer programme, turns the LCP caravan into a simulator. Controllers can practice against computer-generated targets, or more Posts can be plugged in to the command and control network to the point where the entire Bloodhound Force is participating in a single, synthetic exercise. When working up to proficiency, new Controllers are pitted against the Canberras of No 360 Squadron, which attempt to jam the radar. No 100 Squadron - another Canberra target facilities unit - makes mock attacks on missile sites for both training and calibration purposes.

At readiness, the Controller will be constantly searching the assigned Missile Engagement Zone (MEZ) for a hostile target. Not only will the definition of a 'hostile' vary according to the tactical situation, but the MEZ itself will also change in area. For example, one sector may be designated a no-fire zone to allow the safe recovery of friendly aircraft to a nearby aerodrome. In another scenario, all aircraft flying low and at high speed may be regarded as hostile and treated accordingly.

A second combat task will involve the Bloodhound being given instructions to hit a specific target, anywhere within range, by the southern Sector Operations Centre at Neatishead - perhaps the survivor of fighter battle out at sea. Finally, if Neatishead so requires it, the Type 86 radar can be used to provide target information for RAF fighters to augment the dedicated radar chain. The opportunity to practice in a realistic situation occurs when No 11 Group, the whole of Strike Command or even a sizeable portion of NATO hold their regular air exercises in the Elder Forest and Elder Joust series.

Sitting in the dim light of the LCP caravan, the Controller will investigate targets until a hostile subject is found. This is presented on a computer-generated display which filters-out the distracting 'mush' of ground echoes. At the next console, the SNCO technician monitors the health of the missiles, his TV screen displaying a score of parameters for each of the six or eight under the LCP's jurisdiction. Meanwhile, the Controller is checking the signal-to-noise ratio to ensure that the Bloodhound will have a reflected signal strong enough to track. Given elevation and azimuth and range by radar, the computer uses trigonometry to calculate height. If parameters are within limits, 'FREE TO FIRE' is displayed in green on the screen.

When the launch button is pressed, the computer begins to check-out each of the Bloodhounds in turn. A fraction of a second later it will select the first missile found to be fully serviceable and send the launch signal through the two thick cables connecting each to the LCP. Initially, the missile and launcher are 'parented' via signals from the Type 86 radar received by the tall Stalk Aerial on the rear of the launcher. On firing of the four booster rockets, a total thrust of 100,000Ib (45,360kg) - more than a Vulcan at full throttle - shears the bolts connecting Bloodhound and launcher. When it is recalled that the missile itself weighs only, 4,000Ib (1,814kg), the reason for its rapid departure becomes obvious.

Close examination of the radar on its plinth reveals several antennae. There is the large dish-shaped transmitter and small 'orange peel' receiver, plus a small circular Jamming Assessment Aerial (the same as in the Bloodhound's nose) providing the Controller with a subsidiary picture. Nearby, looking like a segment of processed cheese, the In-Flight Reference Aerial sends the Bloodhound a simple of radar energy when it is at high altitude.

A moving target reflects the Type 86's radar energy at a slightly different frequency (the Doppler Effect). Because the receiver in the Bloodhound is also travelling through space, a further apparent shift in frequency is produced. The outcome of this process is predicted by the LCP's computer and the missile instructed to search for a signal of that type. The receiver dish inside its nosecone then turns to lock on to the target, whilst the Bloodhound itself points towards the anticipated point of collision. (In other words, the dish does not point straight ahead except in the rare case of a tail-chase.) The master video screen in the LCP includes a clock count-down to interception time, and if the reflected signal display disappears as this reaches zero, there is no need for the Controller to put his/her head outside to listen for the bang.

If that all sounds very simple. . . it is. That is why the Bloodhound will be around for some years to come, for those who sing the praises of everything new and sophisticated tend to forget it is not only the occasional human who can be described as 'too clever for his own good'. Though straightforward - even primitive in some areas - 'The Dog' is still capable of giving a fatal bite to those who trespass on its domain.

Little did Paul know how little time the “Old Dog” had left when he wrote this article.

Now at 2015 with defence cuts biting, we have no Aircraft Carrier finished, no Harriers, fewer fighters, seriously depleted manpower, and no “Old Dog” to keep watch for us as the guardian of our east coast.

Thought for the year: In 1939 they could build a Wellington Bomber in a day ! Mike

Four seconds later, the four RoF Gosling solid-

Four seconds later, the four RoF Gosling solid-